Aging Current Aging 30 Aging 60 Again 90

Overview and Executive Summary

Getting old isn't nearly equally bad as people think it will exist. Nor is it quite equally practiced.

Getting old isn't nearly equally bad as people think it will exist. Nor is it quite equally practiced.

On aspects of everyday life ranging from mental acuity to physical dexterity to sexual activity to financial security, a new Pew Enquiry Center Social & Demographic Trends survey on crumbling amidst a nationally representative sample of 2,969 adults finds a sizable gap between the expectations that young and middle-aged adults have well-nigh old historic period and the actual experiences reported by older Americans themselves.

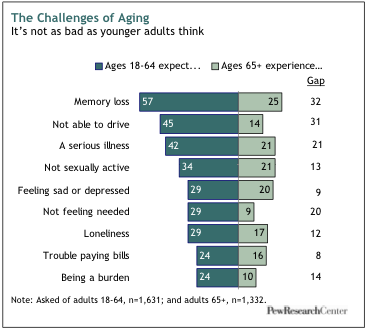

These disparities come into sharpest focus when survey respondents are asked about a series of negative benchmarks oftentimes associated with crumbling, such as illness, memory loss, an inability to bulldoze, an end to sex, a struggle with loneliness and low, and difficulty paying bills. In every instance, older adults report experiencing them at lower levels (often far lower) than younger adults report expecting to encounter them when they abound old.ane

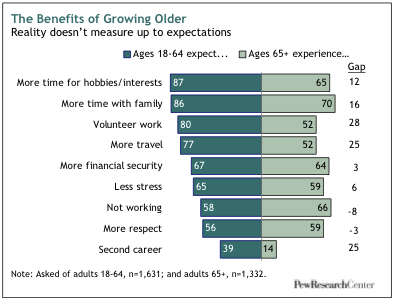

At the aforementioned time, however, older adults report experiencing fewer of the benefits of aging that younger adults await to enjoy when they grow old, such as spending more time with their family unit, traveling more for pleasure, having more than fourth dimension for hobbies, doing volunteer work or starting a 2d career.

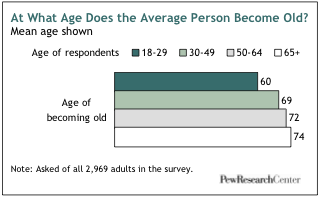

These generation gaps in perception likewise extend to the most basic question of all about one-time age: When does it begin? Survey respondents ages 18 to 29 believe that the average person becomes sometime at age 60. Centre-aged respondents put the threshold closer to 70, and respondents ages 65 and in a higher place say that the average person does non become old until turning 74.

These generation gaps in perception likewise extend to the most basic question of all about one-time age: When does it begin? Survey respondents ages 18 to 29 believe that the average person becomes sometime at age 60. Centre-aged respondents put the threshold closer to 70, and respondents ages 65 and in a higher place say that the average person does non become old until turning 74.

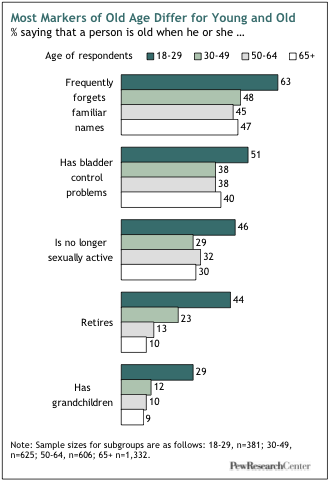

Other potential markers of onetime historic period–such as forgetfulness, retirement, becoming sexually inactive, experiencing bladder control problems, getting gray hair, having grandchildren–are the subjects of like perceptual gaps. For case, well-nigh two-thirds of adults ages eighteen to 29 believe that when someone "oft forgets familiar names," that person is erstwhile. Less than one-half of all adults ages 30 and older agree.

However, a handful of potential markers–failing health, an inability to alive independently, an inability to drive, difficulty with stairs–engender agreement across all generations about the degree to which they serve as an indicator of old historic period.

Grow Older, Feel Younger

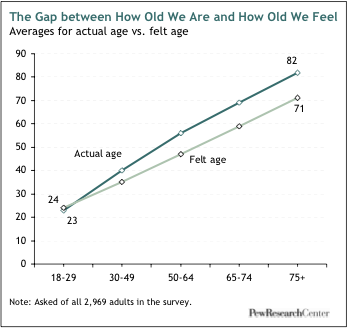

The survey findings would seem to confirm the old saw that you're never too old to feel young. In fact, it shows that the older people get, the younger they feel–relatively speaking. Among eighteen to 29 twelvemonth-olds, about one-half say they feel their historic period, while near quarter say they feel older than their age and another quarter say they experience younger. Past contrast, among adults 65 and older, fully 60% say they feel younger than their historic period, compared with 32% who say they feel exactly their age and just 3% who say they experience older than their age.

Moreover, the gap in years between actual age and "felt age" widens as people abound older. Nearly half of all survey respondents ages 50 and older say they feel at least ten years younger than their chronological age. Among respondents ages 65 to 74, a third say they feel 10 to nineteen years younger than their age, and i-in-six say they experience at to the lowest degree 20 years younger than their actual historic period.

In sync with this upbeat manner of counting their felt historic period, older adults also take a count-my-blessings attitude when asked to look back over the full arc of their lives. Nearly half (45%) of adults ages 75 and older say their life has turned out better than they expected, while but v% say it has turned out worse (the balance say things take turned out the style they expected or have no opinion). All other age groups also tilt positive, simply considerably less so, when asked to assess their lives and so far against their own expectations.

In sync with this upbeat manner of counting their felt historic period, older adults also take a count-my-blessings attitude when asked to look back over the full arc of their lives. Nearly half (45%) of adults ages 75 and older say their life has turned out better than they expected, while but v% say it has turned out worse (the balance say things take turned out the style they expected or have no opinion). All other age groups also tilt positive, simply considerably less so, when asked to assess their lives and so far against their own expectations.

The Downside of Getting Old

To be sure, in that location are burdens that come up with old historic period. About i-in-4 adults ages 65 and older report experiencing memory loss. About one-in-five say they have a serious illness, are not sexually active, or frequently feel lamentable or depressed. Near i-in-six report they are lonely or have trouble paying bills. One-in-seven cannot drive. One-in-10 say they feel they aren't needed or are a burden to others.

But when information technology comes to these and other potential issues related to former age, the share of younger and centre-aged adults who report expecting to encounter them is much higher than the share of older adults who report actually experiencing them.

Moreover, these issues are not as shared by all groups of older adults. Those with low incomes are more than likely than those with high incomes to confront these challenges. The only exception to this design has to do with sexual inactivity; the likelihood of older adults reporting a problem in this realm of life is not correlated with income.

Moreover, these issues are not as shared by all groups of older adults. Those with low incomes are more than likely than those with high incomes to confront these challenges. The only exception to this design has to do with sexual inactivity; the likelihood of older adults reporting a problem in this realm of life is not correlated with income.

Non surprisingly, troubles associated with crumbling accelerate as adults advance into their 80s and beyond. For example, nigh four-in-ten respondents (41%) ages 85 and older say they are experiencing some retentivity loss, compared with 27% of those ages 75-84 and xx% of those ages 65-74. Similarly, 30% of those ages 85 and older say they often feel pitiful or depressed, compared with less than 20% of those who are 65-84. And a quarter of adults ages 85 and older say they no longer drive, compared with 17% of those ages 75-84 and x% of those who are 65-74.

But fifty-fifty in the face of these challenges, the vast majority of the "old old" in our survey announced to accept fabricated peace with their circumstances. Merely a miniscule share of adults ages 85 and older–ane%–say their lives have turned out worse than they expected. Information technology no doubt helps that adults in their late 80s are as likely as those in their 60s and 70s to say that they are experiencing many of the practiced things associated with crumbling–be it time with family, less stress, more respect or more financial security.

The Upside of Getting Old

When asked most a broad range of potential benefits of old age, seven-in-ten respondents ages 65 and older say they are enjoying more time with their family unit. Virtually two-thirds cite more time for hobbies, more financial security and not having to piece of work. About six-in-ten say they become more respect and experience less stress than when they were younger. Just over one-half cite more time to travel and to do volunteer work. Every bit the nearby chart illustrates, older adults may non be experiencing these "upsides" at quite the prevalence levels that almost younger adults expect to enjoy them once they abound old, but their responses nonetheless indicate that the phrase "golden years" is something more than a syrupy greeting card sentiment.

When asked most a broad range of potential benefits of old age, seven-in-ten respondents ages 65 and older say they are enjoying more time with their family unit. Virtually two-thirds cite more time for hobbies, more financial security and not having to piece of work. About six-in-ten say they become more respect and experience less stress than when they were younger. Just over one-half cite more time to travel and to do volunteer work. Every bit the nearby chart illustrates, older adults may non be experiencing these "upsides" at quite the prevalence levels that almost younger adults expect to enjoy them once they abound old, but their responses nonetheless indicate that the phrase "golden years" is something more than a syrupy greeting card sentiment.

Of all the good things about getting quondam, the best by far, co-ordinate to older adults, is being able to spend more than time with family unit members. In response to an open-ended question, 28% of those ages 65 and older say that what they value almost about being older is the run a risk to spend more than time with family, and an additional 25% say that to a higher place all, they value fourth dimension with their grandchildren. A distant tertiary on this list is having more fiscal security, which was cited by fourteen% of older adults equally what they value most about getting older.

People Are Living Longer

These survey findings come at a time when older adults account for record shares of the populations of the United States and most adult countries. Some 39 million Americans, or thirteen% of the U.S. population, are 65 and older–up from 4% in 1900. The century-long expansion in the share of the globe'due south population that is 65 and older is the product of dramatic advances in medical scientific discipline and public health likewise as steep declines in fertility rates. In this country, the increment has leveled off since 1990, but it volition start ascension again when the get-go moving ridge of the nation'southward 76 meg baby boomers plough 65 in 2011. Past 2050, according to Pew Inquiry projections, about i-in-five Americans will be over age 65, and about five% will exist ages 85 and older, up from 2% now. These ratios will put the U.S. at mid-century roughly where Japan, Italian republic and Germany–the three "oldest" large countries in the earth–are today.

Contacting Older Adults

Any survey that focuses on older adults confronts one obvious methodological challenge: A pocket-size merely non insignificant share of people 65 and older are either too ill or incapacitated to take role in a 20-minute telephone survey, or they live in an institutional setting such as a nursing home where they cannot be contacted.2

We presume that the older adults we were unable to reach for these reasons have a lower quality of life, on average, than those we did reach. To mitigate this trouble, the survey included interviews with more 800 adults whose parents are ages 65 or older. We asked these adult children many of the same questions about their parents' lives that nosotros asked of older adults about their own lives. These "surrogate" respondents provide a window on the experiences of the full population of older adults, including those we could not reach directly. Not surprisingly, the portrait of quondam age they draw is somewhat more negative than the 1 painted by older adult respondents themselves. We present a summary of these second-hand observations at the end of Department I in the belief that the two perspectives complement one some other and add texture to our study.

Perceptions virtually Aging

The Generation Gap, Circa 2009. In a 1969 Gallup Poll, 74% of respondents said in that location was a generation gap, with the phrase defined in the survey question equally "a major difference in the point of view of younger people and older people today." When the same question was asked a decade afterward, in 1979, by CBS and The New York Times, just 60% perceived a generation gap. Simply in perhaps the single most intriguing finding in this new Pew Enquiry survey, the share that say at that place is a generation gap has spiked to 79%–despite the fact that there have been few overt generational conflicts in recent times of the sort that roiled the 1960s. It could be that the phrase now means something different, and less confrontational, than it did at the height of the counterculture's defiant challenges to the establishment forty years agone. Whatever the current agreement of the term "generation gap," roughly equal shares of young, middle-aged and older respondents in the new survey agree that such a gap exists. The nigh common explanation offered by respondents of all ages has to do with differences in morality, values and work ethic. Relatively few cite differences in political outlook or in uses of technology.

The Generation Gap, Circa 2009. In a 1969 Gallup Poll, 74% of respondents said in that location was a generation gap, with the phrase defined in the survey question equally "a major difference in the point of view of younger people and older people today." When the same question was asked a decade afterward, in 1979, by CBS and The New York Times, just 60% perceived a generation gap. Simply in perhaps the single most intriguing finding in this new Pew Enquiry survey, the share that say at that place is a generation gap has spiked to 79%–despite the fact that there have been few overt generational conflicts in recent times of the sort that roiled the 1960s. It could be that the phrase now means something different, and less confrontational, than it did at the height of the counterculture's defiant challenges to the establishment forty years agone. Whatever the current agreement of the term "generation gap," roughly equal shares of young, middle-aged and older respondents in the new survey agree that such a gap exists. The nigh common explanation offered by respondents of all ages has to do with differences in morality, values and work ethic. Relatively few cite differences in political outlook or in uses of technology.

When Does Old Historic period Brainstorm? At 68. That'due south the average of all answers from the 2,969 survey respondents. Only as noted higher up, this average masks a wide, historic period-driven variance in responses. More than than half of adults nether 30 say the average person becomes old fifty-fifty before turning 60. But 6% of adults who are 65 or older agree. Moreover, gender besides as age influences attitudes on this field of study. Women, on average, say a person becomes old at age 70. Men, on boilerplate, put the number at 66. In addition, on all 10 of the not-chronological potential markers of old age tested in this survey, men are more inclined than women to say the marker is a proxy for quondam age.

Are You lot Old? Certainly not! Public stance in the aggregate may decree that the average person becomes quondam at historic period 68, but you lot won't get too far trying to convince people that historic period that the threshold applies to them. Amidst respondents ages 65-74, just 21% say they feel onetime. Fifty-fifty among those who are 75 and older, just 35% say they experience onetime.

What Historic period Would You Like to Live To? The average response from our survey respondents is 89. One-in-5 would like to live into their 90s, and 8% say they'd like to surpass the century mark. The public'south verdict on the most desirable life span appears to have ratcheted down a bit in contempo years. A 2002 AARP survey found that the average desired life span was 92.

What Historic period Would You Like to Live To? The average response from our survey respondents is 89. One-in-5 would like to live into their 90s, and 8% say they'd like to surpass the century mark. The public'south verdict on the most desirable life span appears to have ratcheted down a bit in contempo years. A 2002 AARP survey found that the average desired life span was 92.

Everyday Life

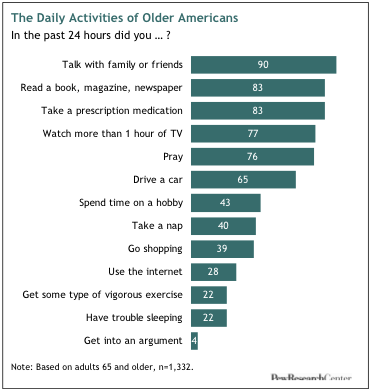

What Do Older People Do Every Day? Amidst all adults ages 65 and older, nine-in-ten talk with family unit or friends every day. About eight-in-ten read a book, paper or magazine, and the same share takes a prescription drug daily. 3-quarters scout more than a hour of telly; nearly the same share prays daily. Nearly two-thirds drive a car. Less than one-half spend time on a hobby. About 4-in-ten take a nap; about the aforementioned share goes shopping. Roughly one-in-iv use the internet, get vigorous exercise or have problem sleeping. Just iv% go into an statement with someone. As adults move deeper into their 70s and 80s, daily activity levels diminish on nearly fronts–specially when it comes to exercising and driving. On the other paw, daily prayer and daily medication both increase with age.

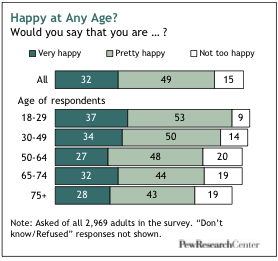

Are Older Adults Happy? They're nigh every bit happy as anybody else. And mayhap more than importantly, the aforementioned factors that predict happiness amongst younger adults–proficient health, practiced friends and fiscal security–mostly predict happiness among older adults. Still, there are a few historic period-related differences in life's happiness sweepstakes. Most notably, in one case all other key demographic variables are held constant, existence married is a predictor of happiness amongst younger adults but not amidst older adults (possibly considering a pregnant share of the latter group is made up of widows or widowers, many of whom presumably accept "banked" some of the key marriage-related correlates of happiness, such as fiscal security and a potent family life). Amid all older adults, happiness varies very little by historic period, gender or race.

Are Older Adults Happy? They're nigh every bit happy as anybody else. And mayhap more than importantly, the aforementioned factors that predict happiness amongst younger adults–proficient health, practiced friends and fiscal security–mostly predict happiness among older adults. Still, there are a few historic period-related differences in life's happiness sweepstakes. Most notably, in one case all other key demographic variables are held constant, existence married is a predictor of happiness amongst younger adults but not amidst older adults (possibly considering a pregnant share of the latter group is made up of widows or widowers, many of whom presumably accept "banked" some of the key marriage-related correlates of happiness, such as fiscal security and a potent family life). Amid all older adults, happiness varies very little by historic period, gender or race.

Retirement and Former Age. Retirement is a place without clear borders. Fully 83% of adults ages 65 and older describe themselves every bit retired, but the word means different things to different people. Just iii-quarters of adults (76%) 65 and older fit the classic stereotype of the retiree who has completely left the working world behind.

An additional 8% say they are retired simply are working part time, while 2% say they are retired but working total fourth dimension and 3% say they are retired simply looking for work. The remaining xi% of the 65-and-older population describe themselves as still in the labor strength, though not all of them have jobs. Whatsoever the fuzziness around these definitions, one trend is crystal articulate from government dataiii: Afterwards falling steadily for decades, the labor force participate rate of older adults began to trend back up nearly x years agone. In the Pew Research survey, the average retiree is 75 years old and retired at age 62.

An additional 8% say they are retired simply are working part time, while 2% say they are retired but working total fourth dimension and 3% say they are retired simply looking for work. The remaining xi% of the 65-and-older population describe themselves as still in the labor strength, though not all of them have jobs. Whatsoever the fuzziness around these definitions, one trend is crystal articulate from government dataiii: Afterwards falling steadily for decades, the labor force participate rate of older adults began to trend back up nearly x years agone. In the Pew Research survey, the average retiree is 75 years old and retired at age 62.

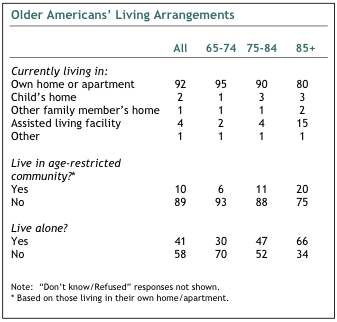

Living Arrangements. More than nine-in-ten respondents ages 65 and older live in thei

r own home or flat, and the vast majority are either very satisfied (67%) or somewhat satisfied (21%) with their living arrangements. Withal, many living patterns change as adults advance into older age. For case, just thirty% of adults ages 65-74 say they live alone, compared with 66% of adults ages 85 and above. Also, but ii% of adults ages 65-74 and 4% of adults ages 75-84 say they live in an assisted living facility, compared with 15% of those ages 85 and above.

Onetime-School Social Networking. The great majority of adults ages 65 and older (81%) say they have people around them, other than family unit, on whom they can rely on for social activities and companionship. About three-quarters say they accept someone they can talk to when they have a personal trouble; six-in-ten say they take someone they can turn to for help with errands, appointments and other daily activities. On the flip side of the coin, three-in-10 older adults say they "oft" assist out other older adults who are in need of assistance, and an boosted 35% say they sometimes practise this. Most of these social connections remain intact as older adults continue to age, but amidst those 85 and to a higher place, the share that say they often or sometimes provide help to others drops to 44%.

Onetime-School Social Networking. The great majority of adults ages 65 and older (81%) say they have people around them, other than family unit, on whom they can rely on for social activities and companionship. About three-quarters say they accept someone they can talk to when they have a personal trouble; six-in-ten say they take someone they can turn to for help with errands, appointments and other daily activities. On the flip side of the coin, three-in-10 older adults say they "oft" assist out other older adults who are in need of assistance, and an boosted 35% say they sometimes practise this. Most of these social connections remain intact as older adults continue to age, but amidst those 85 and to a higher place, the share that say they often or sometimes provide help to others drops to 44%.

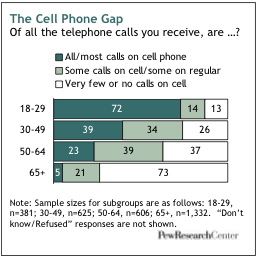

The Twitter Revolution Hasn't Landed Here. If at that place's 1 realm of modern life where one-time and immature behave very differently, it'southward in the adoption of newfangled data technologies. But 4-in-ten adults ages 65-74 utilize the internet on a daily footing, and that share drops to but one-in-six among adults 75 and above. By contrast, iii-quarters of adults ages 18-30 become online daily. The generation gap is even wider when information technology comes to cell phones and text messages. Among adults 65 and older, just v% get virtually or all of their calls on a cell telephone, and just eleven% sometimes use their jail cell phone to transport or receive a text bulletin. For adults nether historic period 30, the comparable figures are 72% and 87%, respectively.

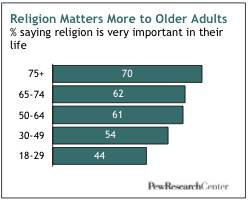

Religion and Old Historic period. Religion is a far bigger part of the lives of older adults than younger adults. 2-thirds of adults ages 65 and older say religion is very important to them, compared with only over one-half of those ages 30 to 49 and simply 44% of those ages 18 to 29. Moreover, amongst adults ages 65 and in a higher place, a third (34%) say faith has grown more important to them over the course of their lives, while but 4% say it has become less of import and the majority (sixty%) say information technology has stayed the same. Among those who are over 65 and study having an affliction or feeling sad, the share who say that religion has get more than important to them rises to 43%.

Religion and Old Historic period. Religion is a far bigger part of the lives of older adults than younger adults. 2-thirds of adults ages 65 and older say religion is very important to them, compared with only over one-half of those ages 30 to 49 and simply 44% of those ages 18 to 29. Moreover, amongst adults ages 65 and in a higher place, a third (34%) say faith has grown more important to them over the course of their lives, while but 4% say it has become less of import and the majority (sixty%) say information technology has stayed the same. Among those who are over 65 and study having an affliction or feeling sad, the share who say that religion has get more than important to them rises to 43%.

Family Relationships

Staying in Bear upon with the Kids. Nearly nine-in-ten adults (87%) ages 65 and older have children. Of this group, just over half are in contact with a son or daughter every day, and an boosted 40% are in contact with at least one child–either in person, past telephone or by email–at least one time a calendar week. Mothers and daughters are in the most frequent contact; fathers and daughters the least. Sons autumn in the middle, and they keep in touch with older mothers and fathers at equal rates. Overall, iii-quarters of adults who take a parent or parents ages 65 and older say they are very satisfied with their relationship with their parent(s), but that share falls to 62% if a parent needs help caring for his or her needs.

Was the Great Bard Mistaken? Shakespeare wrote that the terminal of the "seven ages of man" is a second childhood. Through the centuries, other poets and philosophers have observed that parents and children oft reverse roles as parents grow older. Non and then, says the Pew Research survey. Just 12% of parents ages 65 and older say they by and large rely on their children more their children rely on them. An additional fourteen% say their children rely more on them. The majority–58%–says neither relies on the other, and 13% say they rely on ane another equally. Responses to this question from children of older parents are broadly similar.

Intergenerational Transfers within Families. Despite these reported patterns of non-reliance, older parents and their adult children do help each other out in a multifariousness of ways. However, the perspectives on these transfers of money and time differ by generation. For example, most one-half (51%) of parents ages 65 and older say they have given their children money in the by year, while merely xiv% say their children take given them coin. The intra-family accounting comes out quite differently from the perspective of adult children. Amid survey respondents who have a parent or parents ages 65 or older, a quarter say they received money from a parent in the past year, while an nearly equal share (21%) say they gave money to their parent(s). There are similar deviation in perception, past generation, about who helps whom with errands and other daily activities. (To be clear, the survey did not interview specific pairs of parents and children; rather, it contacted random samples who fell into these and other demographic categories.) Not surprisingly, every bit parents advance deeper into old historic period, both they and the adult children who take such parents report that the balance of aid tilts more toward children helping parents.

Intergenerational Transfers within Families. Despite these reported patterns of non-reliance, older parents and their adult children do help each other out in a multifariousness of ways. However, the perspectives on these transfers of money and time differ by generation. For example, most one-half (51%) of parents ages 65 and older say they have given their children money in the by year, while merely xiv% say their children take given them coin. The intra-family accounting comes out quite differently from the perspective of adult children. Amid survey respondents who have a parent or parents ages 65 or older, a quarter say they received money from a parent in the past year, while an nearly equal share (21%) say they gave money to their parent(s). There are similar deviation in perception, past generation, about who helps whom with errands and other daily activities. (To be clear, the survey did not interview specific pairs of parents and children; rather, it contacted random samples who fell into these and other demographic categories.) Not surprisingly, every bit parents advance deeper into old historic period, both they and the adult children who take such parents report that the balance of aid tilts more toward children helping parents.

Conversations nearly Stop-of-Life Matters. More than three-quarters of adults ages 65 and older say they've talked with their children about their wills; almost ii-thirds say they've talked about what to practise if they can no longer make their own medical decisions, and more than half say they've talked with their children about what to do if they can no longer live independently. Similar shares of adult children of older parents study having had these conversations. Parents and adult children concord that it is the parents who by and large initiate these conversations, though 70% of older adults study that this is the example, compared with just 52% of children of older parents who say the same.

Conversations nearly Stop-of-Life Matters. More than three-quarters of adults ages 65 and older say they've talked with their children about their wills; almost ii-thirds say they've talked about what to practise if they can no longer make their own medical decisions, and more than half say they've talked with their children about what to do if they can no longer live independently. Similar shares of adult children of older parents study having had these conversations. Parents and adult children concord that it is the parents who by and large initiate these conversations, though 70% of older adults study that this is the example, compared with just 52% of children of older parents who say the same.

About the Survey

Results for this report are from a telephone survey conducted with a nationally representative sample of 2,969 adults living in the continental The states. A combination of landline and cellular random digit dial (RDD) samples were used to cover all adults in the continental United States who have admission to either a landline or cellular telephone. In add-on, oversamples of adults 65 and older as well as blacks and Hispa

nics were obtained. The black and Hispanic oversamples were achieved by oversampling landline exchanges with more black and Hispanic residents every bit well every bit callbacks to blacks and Hispanics interviewed in previous surveys. A total of two,417 interviews were completed with respondents contacted by landline phone and 552 with those contacted on their cellular phone. The data are weighted to produce a terminal sample that is representative of the general population of adults in the continental United States. Survey interviews were conducted under the direction of Princeton Survey Research Associates (PSRA).

- Interviews were conducted February. 23-March 23, 2009.

- There were 2,969 interviews, including 1,332 with respondents 65 or older. The older respondents included 799 whites, 293 blacks and 161 Hispanics.

- Margin of sampling mistake is plus or minus 2.half dozen percentage points for results based on the total sample and 3.7 percentage points for adults who are 65 and older at the 95% confidence level

- For data reported by race or ethnicity, the margin of sampling mistake is plus or minus 3.5 percentage points for the sample of older whites, plus or minus seven.four percentage points for older blacks and plus or minus 10.3 pct points for older Hispanics.

- Note on terminology: Whites include only non-Hispanic whites. Blacks include simply non-Hispanic blacks. Hispanics are of any race.

Almost the Focus Groups

With the assistance of PSRA, the Pew Research Center conducted four focus groups before this year in Baltimore, Doctor. Two groups were made up of adults ages 65 and older; two others were fabricated up of adults with parents ages 65 and older. Our purpose was to listen to ordinary Americans talk well-nigh the challenges and pleasures of growing quondam, and the stories nosotros heard during those focus groups helped us shape our survey questionnaire. Focus group participants were told that they might exist quoted in this report, but we promised not to quote them by name. The quotations interspersed throughout these pages are drawn from these focus group conversations.

Well-nigh the Report

This report was edited and the overview written by Paul Taylor, executive vice president of the Pew Research Center and director of its Social & Demographic Trends project. Sections I, Ii and Three were written by Senior Researcher Kim Parker. Section Four was written by Inquiry Associate Wendy Wang and Taylor. Section V was written by Senior Editor Richard Morin. The Demographics Department was written past Senior Writer D'Vera Cohn and the data was compiled by Wang. Led by Ms. Parker, the full Social & Demographic Trends staff wrote the survey questionnaire and conducted the analysis of its findings. The regression analysis nosotros used to examine the predictors of happiness among older and younger adults was done past a consultant, Cary Fifty. Funk, associate professor in the Wilder Schoolhouse of Government at Virginia Commonwealth University. The report was copy-edited by Marcia Kramer of Kramer Editing Services. Information technology was number checked past Pew Enquiry Center staff members Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, Daniel Dockterman and Cristina Mercado. We wish to thank other China colleagues who offered research and editorial guidance, including Andrew Kohut, Scott Keeter, Gretchen Livingston, Jeffrey Passel, Rakesh Kochhar and Richard Fry.

Read the full report for more details.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2009/06/29/growing-old-in-america-expectations-vs-reality/

0 Response to "Aging Current Aging 30 Aging 60 Again 90"

Post a Comment